“I could not attempt an official history, but in all histories, we miss the small personal details, the odd incidents that often give us a clearer picture of how things were than all the match reports and minutes of meetings. The ordinary club members are the raison d’etre of our organization, so it seems appropriate to record a few of their experiences.”

Letter from EC Baker to Kevin Thurlow

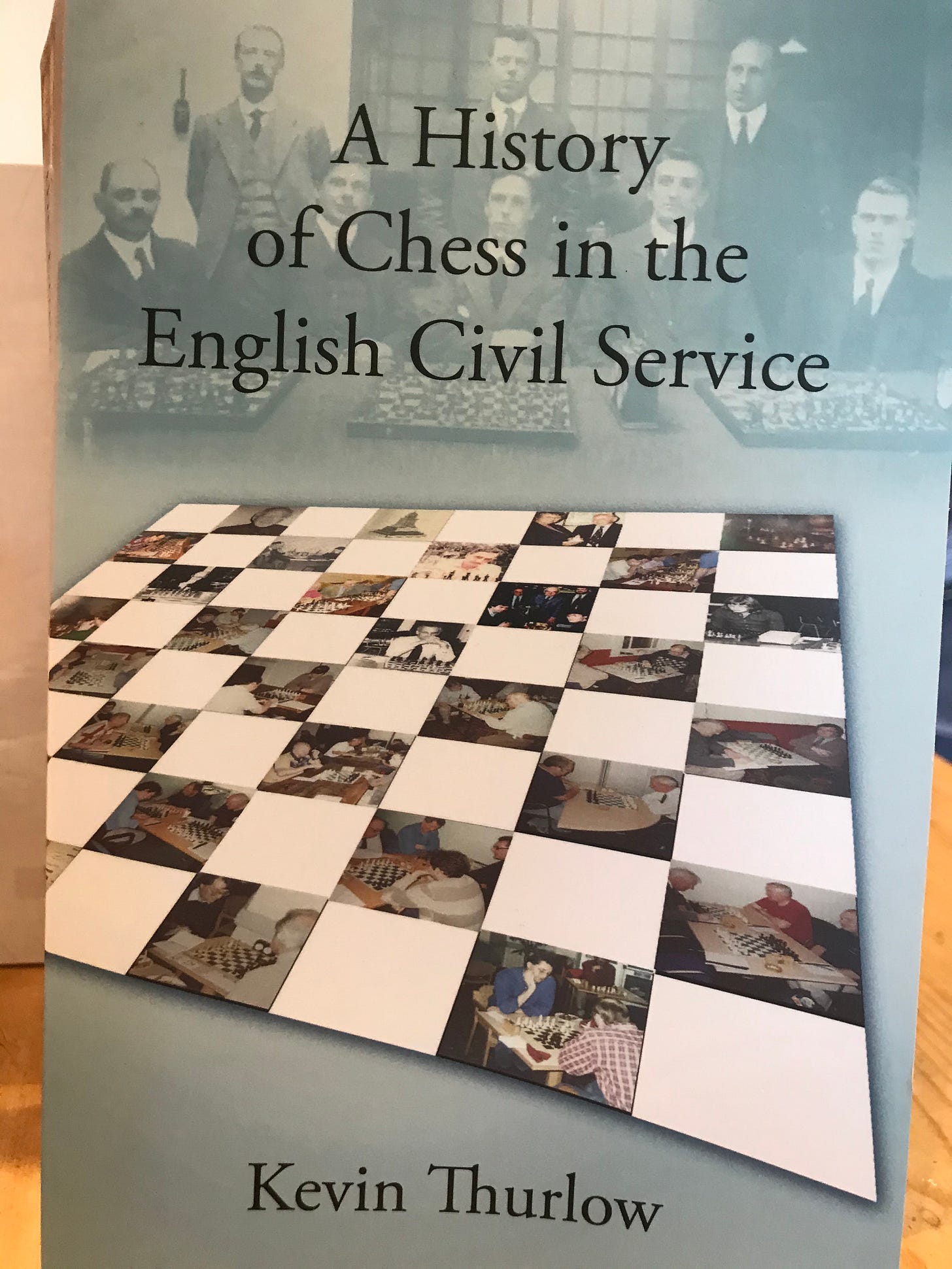

For over a hundred years, the Civil Service Chess League played a crucial role in England’s chess heritage. Formed in 1904, the League reached its zenith in the 1960s, before declining in the twenty-first century as changing working patterns, the rise of the internet and increased leisure options all took their toll.

Kevin Thurlow highlights that, “The glory days have long gone, but those involved will never forget them.” His book is a fitting tribute to those times, which will be enjoyed by all chess-players, irrespective of whether they have a specific connection to the Civil Service.

Kevin Thurlow is a well-respected career civil servant and chess writer. He has played a key part in the Civil Service League as a player and administrator over many years. The insights he has gleaned as participant, witness, and keen historian, ensure he is perfectly placed to write this book. A venture made possible because of a generous donation from an anonymous benefactor, who we should all be grateful to.

Much of what goes on in our clubs and leagues across the country feels so vital and fresh in the moment but is at risk of being forgotten if not properly recorded. Kevin has done much to ensure that the chess in the Civil Service avoids this fate in his substantial (527 page) volume. Through seven key chapters charting the story of the League from its beginnings, through to the second world war, subsequent modernization, “Drama follows Drama” and ultimately “Decline and Fall.” Significant annexes are also provided, which include individual club histories, biographies and records of trophy winners and officials.

I was fascinated to learn that Prime Minister Bonnar-Law was a chess enthusiast who presented the trophy to the winner of the Parliamentary chess tournament and that many years later a successor, Jim Callaghan, awarded the prizes at Hastings. Bonnar-Law described chess as being like a “Cold bath for the mind,” and Civil Service chess frequently had supporters in high places. In 1937 Chancellor Sir John Simon lobbied to ensure that the House of Commons chess room should remain close to the dining-room and the smoking room. The Minister of Transport, Dr Burgin, said “Of chess it has been said that life is not long enough for it – but that is the fault of life, not chess.” Chess was destined to remain the only official game of the House of Commons, as Thurlow points out, to the disappointment of the Billiards players.

The History of Chess in the English Civil Service is particularly good on chess in the second world war. A time when many excellent chess players, including Alexander, Golombek and Aitken were working as codebreakers at Bletchley. Thurlow notes that Turing himself, “…was enthusiastic about chess but not very good… Golembeck used to give him queen odds or turn the board round when Turing resigned and win from that position.” Jack Good, a fellow Bletchley recruit thought the problem was that “…Turing was too intelligent to play the obvious move and tried to work everything out from first principles.” When Bletchley beat Oxford University in 1944, Thurlow highlights that: “People must have been curious as to why a small place like Bletchley had such a massively strong chess club. The prevailing attitude then was to realize they were engaged in secret work and not to ask questions.”

The post-war Civil-Service League challenges Thurlow excellently documents, in many ways mirror those seen elsewhere in our game. From the case of the player who had been graded 200 relatively recently entering (and unsurprisingly) winning the U-120 section of an event, through to disputes over the meaningfulness of grades when selecting a team order, much that we would take for granted today was once not so clear cut. I found it astonishing to learn that as late as 1977 it was deemed acceptable in some quarters for a player to participate in two matches simultaneously. I was somewhat less surprised to read that the proposed Civil Service broken chess clock auction did not prove to be particularly successful.

Some of the other stories Thurlow retells, from drunkenness at the board through to the player who lost in a winning position and promptly burst into tears (before his kind-hearted opponent said the game could be a draw) bring back to life some very vivid happenings. We all probably know someone in our own clubs a bit like the civil service player who appealed against his grade, by resubmitting his results to the graders without a couple of the losses. The graders proved equally to this attempted deception.

Thurlow highlights that evidence of a changing society could be seen in the Civil Service chess world. For instance, through an increasing determination for players to want to challenge adjudication decisions, where once deference to authority had been paramount. Moreover, adjudicators themselves who had once “been rewarded” with twenty packets of cigarettes, ultimately wanted cash for their labours. As with most other Leagues, decline would come, and it is a little sad to read about this. The 1960s hey-day of nine divisions and many of the country’s leading chess players being civil servants would not last forever. That said, in its new open format, play continues under the guise of the London Public Service League to this day.

A History of Chess in the English Civil Service is an important book. All chess historians and anyone who might be thinking about documenting the history of their own League should certainly read it. However, anyone who enjoys chess will derive pleasure from this work. If I had one suggestion for a future print-run, it would be to add a section with a few games from the Civil Service League, as that would further broaden the appeal of this excellent contribution.

Kevin Thurlow has done a terrific job, which does the memory of all who played in the Civil Service Chess League proud.

" .... in all histories, we miss the small personal details, the odd incidents that often give us a clearer picture of how things were than all the match reports and minutes of meetings."

How true! Many years ago I wrote an on-line article about my school club's experiences competing in an otherwise adult local chess league during the 1960s. Determined to avoid the bland approach so often encountered in such writings, I put in everything, including criticisms of players, both our own and opposing (but without naming names except for the most egregious instances).

My only regret is that I never got round to completing an intended companion piece about the league itself in that era, and some of its best-known characters. The target readership is mostly deceased now.